If you are living with a terminal illness, you are at risk of developing pressure sores (pressure ulcers). It’s best to prevent pressure sores, because they can take a long time to heal. On this page, we explain things you can do to help prevent pressure sores and ways to manage them if they do develop.

What are pressure sores?

On this page, we use the words pressure sores to talk about skin damage caused by pressure. You may call them pressure sores, or hear them called pressure ulcers, pressure damage, bedsores, or pressure injury.

Pressure sores are damaged areas of skin or tissue under the skin. They are most common over bony parts of the body, where your body might rest against a chair or bed.

There are different categories of pressure sores. These range from intact skin that may be discoloured or painful, to open sores or wounds that affect the tissue under the skin. They may develop gradually over time or more quickly, over a few hours or less.

Who is at risk of pressure sores?

Your health and social care team should regularly assess your risk of getting pressure sores.

Anyone can develop pressure sores. You are more at risk if you:

- find it hard to move – for example, because of age, illness, an underlying medical condition, or recent surgery

- cannot change your position without help

- cannot feel sensations, including pain, in part or all of your body

- have a poor appetite or diet, do not drink enough water, or both

- have trouble controlling your bladder or bowel (incontinence)

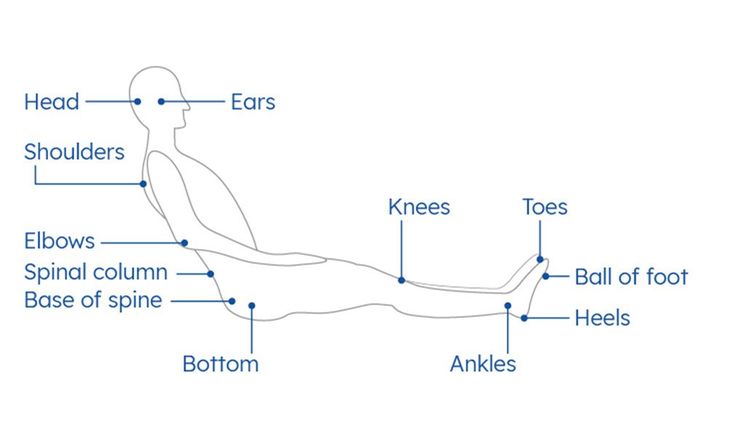

- have damage to your spinal cord, and cannot move or feel the areas shown in the picture below

- have a medical condition that affects blood supply, makes skin more fragile, or makes it more difficult to move – for example, diabetes or problems with circulation to your legs and feet

- have had pressure damage before.

What parts of the body are most at risk of pressure sores?

Pressure sores are most likely to develop where a part of the body has contact with a surface for a long time. You're most likely to get pressure sores on your:

- head

- ears

- shoulders

- elbows

- spinal column (the bone in the middle of your back)

- base of spine (lower back)

- knees

- ankles

- toes

- balls of feet

- heels.

These areas are at risk when you are sitting up and when lying in bed. The labels on the picture below show the body parts where pressure sores may develop.

Body parts most likely to be affected by pressure sores.

What are the signs of pressure sores?

You may have one or more of these signs of a pressure sore:

-

Discoloured patches of skin:

-

If you have a lighter skin tone, you may get red patches.

-

If you have a darker skin tone, you may get purple or blue patches, or patches that are a different colour than the surrounding area – usually darker.

-

-

Discoloured patches of skin that do not fade when you press them. Your doctor or nurse may use a clear glass to see the colour of the skin, or press the skin gently with a finger for three seconds.

-

An area of skin that is a different temperature or feels harder or softer than the surrounding skin.

-

Swelling, pain or itchiness in the affected area.

If the skin damage gets worse, it may develop into:

- an open wound or blister

- a wound that affects the deeper layers of tissue under the skin

- a wound that reaches the muscle or bone.

What causes pressure sores?

Pressure sores are caused by blood supply to the skin being reduced, after the skin is under pressure for a long time. It is usually caused by:

- sitting or lying in one position for too long without moving or

- a device, such as a catheter bag strap or oxygen mask, pressing against your skin for a long time.

Pressure sores can develop after only a few hours, whether you are in hospital, a hospice, a care home or living at home. Or they may develop gradually over time.

Ways to prevent pressure sores

The most important thing you can do to avoid pressure damage is follow the practical guidance in the SSKINS checklist below. Your health and social care team may also follow local guidelines or policies.

SSKINS checklist

The SSKINS approach is one tool for preventing and treating pressure sores. It may be that not every suggestion in this checklist is suitable for you. Talk to your doctor, nurse or another healthcare professional to find out what will work best for you.

S - Skin checks

Noticing any skin changes at an early stage can help prevent skin damage getting worse.

Checking your skin:

- Check your skin for signs of damage at least twice a day – once before getting up, and once later in the day or before you go to bed at night.

- If you use medical devices, such as oxygen or feeding tubes and surgical drains, it is important to check the skin under these devices.

- You may find using a mirror is helpful to check different areas. Or you could ask for the help of a carer or someone you trust.

If you find any changes, it’s important to speak with your doctor, nurse or another healthcare professional as soon as possible. You could write down if you notice any changes in:

- skin colour

- skin temperature

- swelling

- hardness or softness compared with surrounding skin.

S - Surface

Surface means anything your skin is in contact with for a length of time without moving. It could be something you are lying or sitting on. You can use various aids, cushions and mattresses to help redistribute pressure on your skin. Ask your doctor, nurse or healthcare professional for advice about what might work for you.

Here are some things you could try:

- Use a foam or air mattress – one that is made for preventing pressure sores.

- If you spend a lot of time sitting down, use a cushion that evenly distributes pressure on your skin.

- Place pillows in between your ankles and knees when in bed.

- Use a lightweight duvet cover or blankets on your bed.

- Try to avoid sitting on any area of skin that is red or discoloured.

- Avoid using hot water bottles or heated pads against skin that is red or discoloured.

- Try to make sure you are not sitting or lying on any medical equipment, such as drainage tubes.

K - Keep moving (if you can)

Try to change your position regularly when you are in bed or sitting down. Your doctor, nurse, or another healthcare professional can talk to you about how often you should try to move.

Changing position and moving around might include:

- moving from one buttock to another when sitting

- moving from lying on your back to lying on your side when in bed – even a slight tilt can make a difference.

Small changes to your lifestyle can make a big difference. For example, if you can, try getting up and walking around during television advert breaks.

If you are caring for someone who needs your help to change position, you may be able to use aids such as a slide sheet or standing aid. It’s important to ask a health or social care professional for advice before moving someone.

Your health and social care team should give you information about how to use any equipment, such as mattresses or cushions. If you have any questions or worries, ask them for more information.

I - Incontinence (or moisture)

Incontinence means you may not have control over your bladder, bowels, or both. If left in contact with the skin, pee and poo (urine and faeces) can irritate or damage it. This can cause the skin to become weaker, which may increase the risk of pressure damage.

There are things you can do to reduce this risk:

-

Try to keep your skin dry. Be aware of moisture building up between the buttocks and in the rest of the genital area. Moist skin can increase the risk of skin damage, especially if your skin is damp due to:

-

not being properly dried

-

incontinence

-

sweat

-

a wound that is weeping.

-

-

Change incontinence pads and clean the skin as soon as possible when wet or dirty.

-

Ask your doctor, nurse or another healthcare professional about using barrier creams.

If you have any problems with your bladder or bowels, ask a healthcare professional for help and advice. At home, this might be a district nurse or GP. In hospital or a hospice, this could be your ward staff.

N - Nutrition and hydration (eating and drinking)

- Try to eat a healthy diet. If you are unable to eat large meals, it can be better to eat small meals more often.

- There are drinks and food supplements available that have added calories or protein. If you think you may need these, speak to your GP about what might be suitable for you.

- Try to drink up to eight glasses or cups of fluid per day. This will help to keep your skin hydrated. Drinks might include water, tea or coffee.

S - Selfcare or shared care

It’s important that everyone involved in your care knows what makes you more likely to develop pressure damage. Everyone needs to recognise the risks and try to make any of the necessary changes.

If you have diabetes or problems with circulation to your legs and feet, you have a higher chance of developing pressure damage. It’s important that you, your healthcare team, and anyone else caring for you recognises this risk. You and the people caring for you can try different ways to prevent pressure damage, including the things we talk about on this page.

If you have had, or do have, pressure damage, it is important that everyone involved in your care knows. Tell them about any equipment you use, to make sure they can recognise the risks and make any necessary changes to your care.

Ways to manage pressure sores

Looking after damaged skin:

- If an area of your skin is discoloured or broken, try to avoid sitting or lying on the area.

- Keep the skin clean and dry. Pat your skin to dry it instead of rubbing, and make sure it is completely dry.

- Make sure you check anywhere skin meets skin, such as under breasts or in the genital area. Keep them clean and dry.

- Do not rub or massage the skin.

- Do not use talcum powder or perfumed toiletries.

Your health and social care team will also help you manage pressure sores. This may include:

- covering the pressure sore with a suitable dressing – your doctor, nurse, or another healthcare professional can advise you on this

- pain relief – you may need to take medication or have anaesthetic cream applied to your pressure sore dressings

- helping you to change position regularly

- helping you to eat a balanced diet and drink enough fluid, or give artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) if that’s what you use

- improving the pressure relieving equipment, such as mattresses or cushions, you use

- complementary therapies and emotional support – you may get comfort from music, touch, relaxation, distraction or a therapy animal.

Pressure sore treatment is to make you comfortable and prevent any further skin damage. It can help to tell your health and social care team how pressure sores are affecting you and what’s important to you. For example, if you find it painful to have your dressings changed, they might suggest you have pain relief beforehand, try using a different dressing or change the dressing fewer times.

Your health and social care team should check any pressure sores regularly. This should happen each time they change a dressing and at least weekly. Tell your health and social care team if the pressure sore is getting worse, is causing pain, or smells (has an odour).

Your health and social care team will either have, or can request, the dressings, creams and medications you need.

If pressure sores are not managed or treated, you may have further complications that can be harmful, such as an infection. In extreme cases, some of these complications may need treatment in a hospital or have a longer-term impact on your quality of life.

Pressure sores towards end of life

Towards the end of the life, there is a greater risk of developing pressure sores. This is because you may not be moving around or eating and drinking as much. Incontinence can also damage the skin, making it harder to keep skin dry. The skin becomes less able to repair itself. But you, and the people supporting you, can still follow the guidance on this page to help prevent pressure sores at this time.

If you develop a pressure sore towards the end of life, the focus of treatment will be about making sure you are comfortable, rather than healing the pressure sore.

Getting support with pressure sores

If you notice any changes to your skin, it’s important to speak with your doctor, nurse or another healthcare professional as soon as possible. You can also follow the guidance on this page to help look after the affected skin.

You should contact your health and social care team if you have any signs of infection such as:

- swelling

- pus coming from the pressure sore

- cold skin and a fast heartbeat

- severe or increasing pain

- a high temperature

- change in skin colour:

- on lighter skin tones you may see redness

- on darker skin tones you may see an area of skin that’s purple, blue, or different in colour to the surrounding skin – usually darker.

Your doctor or nurse may refer you to a tissue viability nurse (TVN). TVNs specialise in wound care. They can assess you and make a care plan to manage your pressure sores.

The TVN or another healthcare professional should record the level of skin damage (the category or grade) and report any pressure sores with an open wound to a central database. This database is part of a national effort to measure the impact of pressure sores and improve patient safety. If you have any questions about this, it’s best to speak with your health and social care team.

If you, or someone supporting you, would like some emotional support, you can call our free Support Line on 0800 090 2309 or email support@mariecurie.org.uk.

We also have an Online Community where you can share your experience, and give and get support from other people in a similar situation. Visit community.mariecurie.org.uk.